The General Data Protection Regulation, better known under its acronym GDPR, has now been active as of half a year. The GDPR greatly limits the collection, storage and publication of personal data. That means that, although it is not perfect yet, privacy really is on everyone’s mind nowadays. At Openprovider, we can imagine that many resellers and website owners are curious to know how much the GDPR has truly achieved on the topic of domain spam. Is it still possible to receive this?

Recently, we investigated two unrelated domain-related spam complaints from two of our most valued customers. Does that mean that we leak personal data somewhere? This blog post explains how the whois is protected, and tries to understand the smart minds of personal data harvesters after the GDPR.

A quick explanation

Within the scope of domain registration, the biggest impact affects the whois of generic top level domains (gTLDs). We will briefly explain those two terms, which are important for understanding the scope of this blog post.

- The whois is a data directory that registries and/or registrars maintain. It contains the registration data of each domain name. The whois stores personal and company data, including the domain name, domain status, expiration date, registrar and domain contacts.

- A gTLD is any domain extension that is not a country code. For example: .com is a gTLD, .uk is not; .info is a gTLD, .cn is not; .berlin is a gTLD, .de is not; .eu is… well, even registry EURid does not know, but at least ICANN does not control .eu, so we consider it a country code. Country codes always have 2 characters. Each extension that has 3 or more characters is a gTLD.

We do not cover the ccTLDs (country code top level domains). In most cases, their whois service was already quite restricted before the enforcement date of the GDPR.

The era of unrestricted, open whois

ICANN has always enforced an open whois in its contracts with registries and registrars. All contact data of the domain owner, administrative contact and technical contact were visible, without any restrictions. That’s great in many cases. For example, if you want to contact the domain holder because you want to buy his domain; if you want to contact the domain’s technical contact because the nameservers are broken; if you’re doing statistical research; or if you are a trademark lawyer and want to contact the domain holder of a domain that infringes a trademark.

On the other hand, the publication of personal data also comes with potential abuse. A prime minister does not want the whole world to know his telephone number. And the domain holder of a strongly polarising website does not want his opponents to visit his home address. Moreover, no registrants of any website wants third parties to flood them with unsolicited offers of web design or SEO services.

This last example is what this blog post is about.

A short note on how easy it was to get all data from just registered domains: gTLDs are required to open their zone files to almost everyone. I could (and still can), at any moment, get a full list of all registered domain names in the gTLD zone and start crawling the whoises to retrieve linked e-mail addresses. With almost 200.000.000 registered gTLDs, this is a very valuable data source. If I do it daily, I can easily find all domains registered within the last 24 hours.

The era of restricted whois

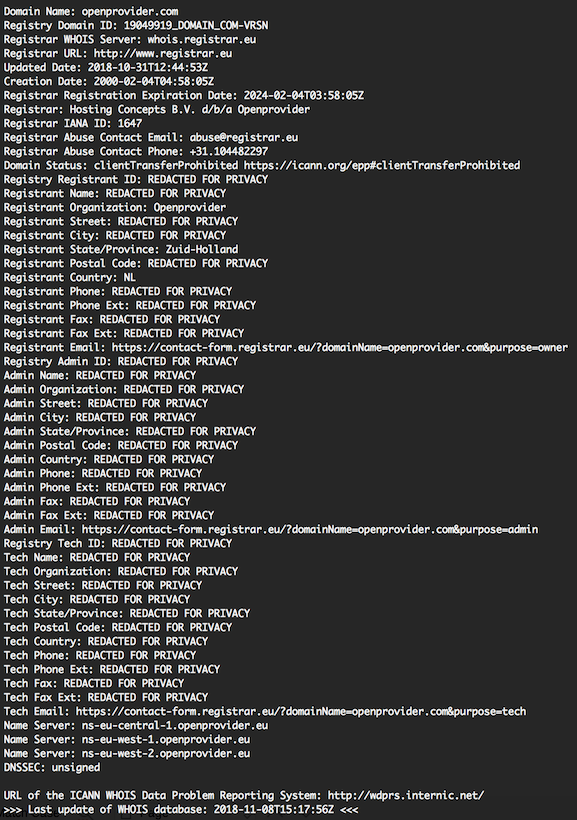

Since the GDPR is enforced, the contact data that are publicly visible through the whois are limited to company name, state/province and country code. Moreover, the whois includes an anonymised e-mail address or a link to a contact form. As an example, you can view the whois output of openprovider.com on the right. You can click on the image to enlarge it.

In other words: there is no relation anymore between a domain name and contact e-mail address. Nobody can find the domain holder’s e-mail address from the whois data of the respective domain name.

So, the GDPR finally got rid of domain spam!?

Theoretically, as the GDPR limits the whois to the most basic information, old domain spam practices are no longer possible. However, theory is not always equal to the real life situation…

Recently, we investigated two unrelated questions from two of our most valued customers. Both customers complained about domain-related spam to the domain holder, shortly after registration of a new domain.

Their justified question was: is Openprovider leaking data? The answer is “no”. We were able to drill down each single case to a logical explanation.

Fact: the data is not published anywhere

What are the potential leaks? Of course there is our own whois server, which ICANN requires us to run. We can assure you: we do not leak data there. The “REDACTED FOR PRIVACY” fields are hard-coded in our implementation. We did not yet implement a way to disclose whois data for eligible requesters.

That leads us to the registry whois server. Most cases we saw concerned .com and .net domains. Again, we can assure you that no data is leaking there. Verisign, the registry for .com and .net, does not even support contact objects in their registry system! In other words, we never send contact data to Verisign.

Other registries do run their own whois server, including contact data stored in their systems. But just like us, those registries are bound to ICANN rules. Immediately from the 25th of May 2018, these registries hid the personal data fields. We cannot guarantee this for all gTLD registries, but the complaints are about the biggest ones: .org, .biz, .info and just one other domain under .art. So while we cannot speak for all of them, that should not be a source for leaking.

A short note on the difference between collection and publication. The GDPR so far only affects published data. Under the hood, the registrar en most registries still collect full contact data. Openprovider also shares this data with a designated escrow agent as part of ICANN’s requirements. However, publication is strictly limited.

Other potential sources require illegal actions. Of course, third parties may hack our systems, registry systems or the data escrow provider – or that might happen to your systems. However, all of this is extremely unlikely.

Looking at all the above, well, it’s quite unlikely that domain spam happens on such a big scale because of source data being available.

Assumption: what happened?

All cases that we investigated can be divided in three scenarios, of which the second and third are most likely to happen on a big scale. For full understanding, it’s important to know that the registries’ zone files are still available. If you want, you can download a fresh list of domains every day, and you then know which domains have been registered during the last 24 hours.

- Some websites clearly show contact details. If you register domain-x.com place a big banner “Contact us at information@domain-x.com!” on it, you deliberately choose to disclose your personal data.

- Spammers may use standard addresses. If you want to contact the owner of www.domain-y.com, just try sending an e-mail to info@domain-y.com.

- But most likely, spammers use professional service providers like domaintools.com or whoxy.com. Those providers have decades of history on millions of domains, including personal data from the pre-GDPR era. While in our opnion, they should not be allowed to store and publish it, it is a fact they still do so and that people use these data. We will provide some examples on this.

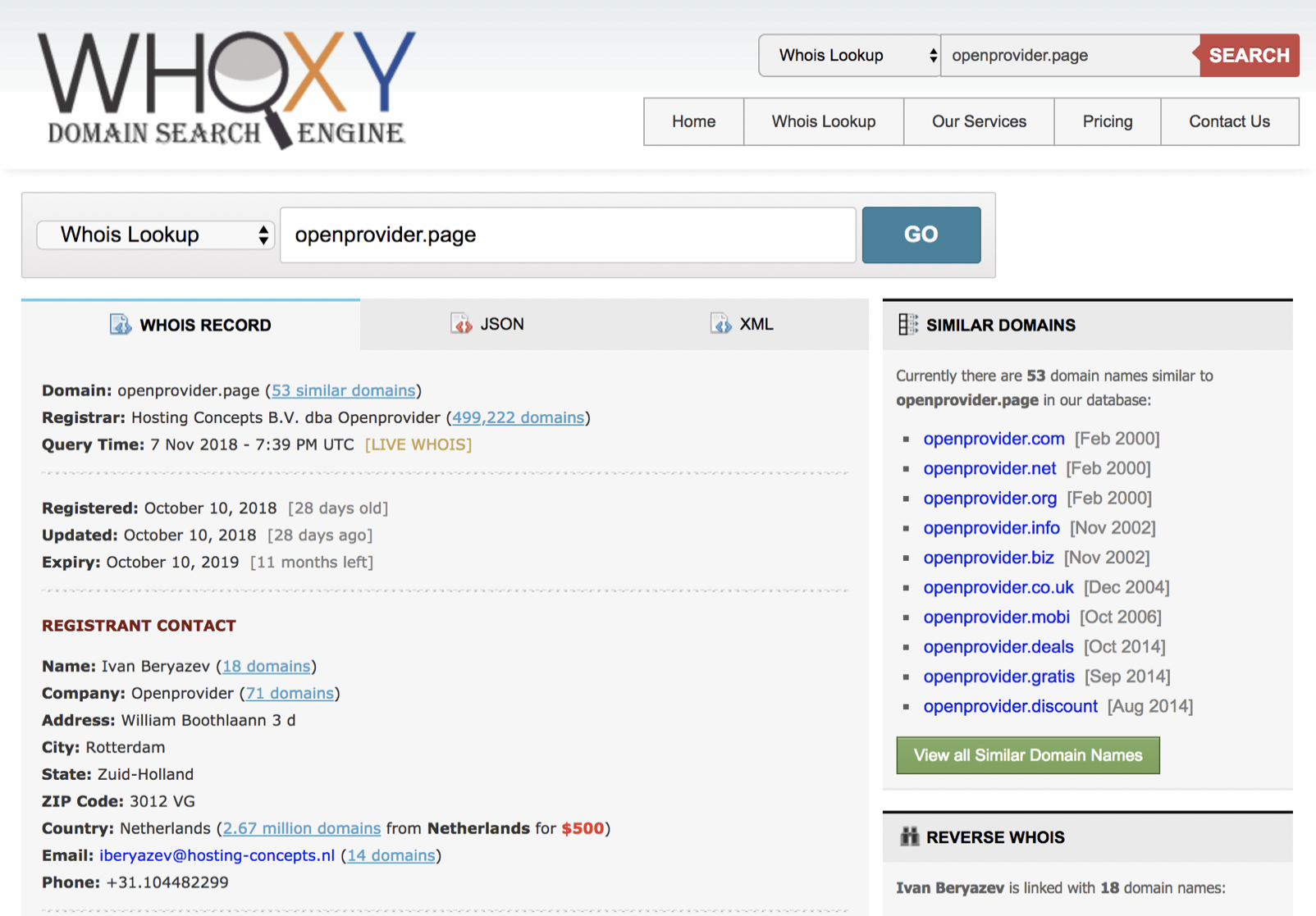

Example 1: openprovider.page

We registered the domain openprovider.page this year on the 10th of October this year. The company name is Openprovider, and the address is our current office address (Kipstraat in Rotterdam). This, of course, is is invisible in the whois.

However, the details that we can see here are an address where we moved away around 15 years ago. The contact is also not the person actually linked to the domain, and all other personal data are incorrect as well.

Looking up this domain on Whoxy.com, they claim to know the holder’s personal details.

These data likely come from an older domain (probably a test domain), that we reigstered on the name of “Openprovider” as well.

Example 2: incorrect historical match

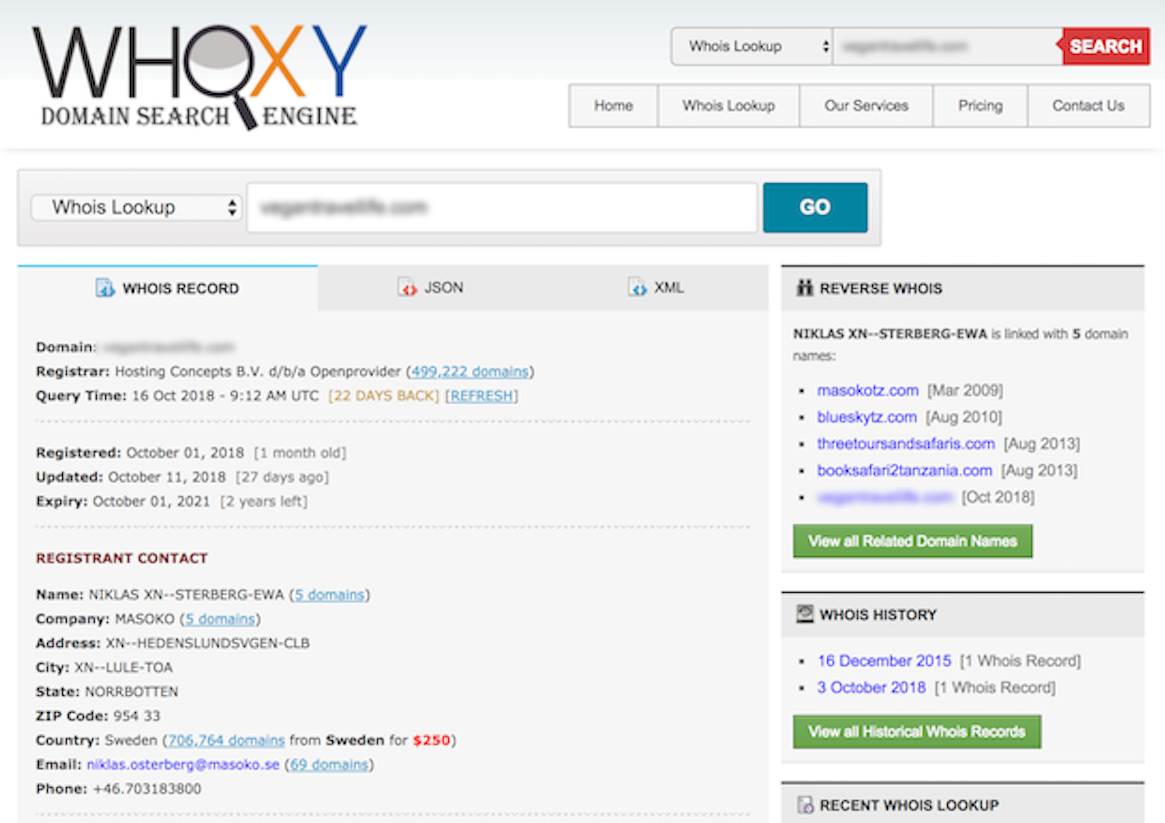

The second example (which concerns an unaware end user, so we will not be sharing the name) strengthens our assumptions. The public whois shows that the domain belongs to the Dutch company “Masoko”. Whoxy.com (we don’t have shares in that company!) correctly shows “Masoko” as the owner. But the contact data are those of a completely unrelated Swedish company with the same name.

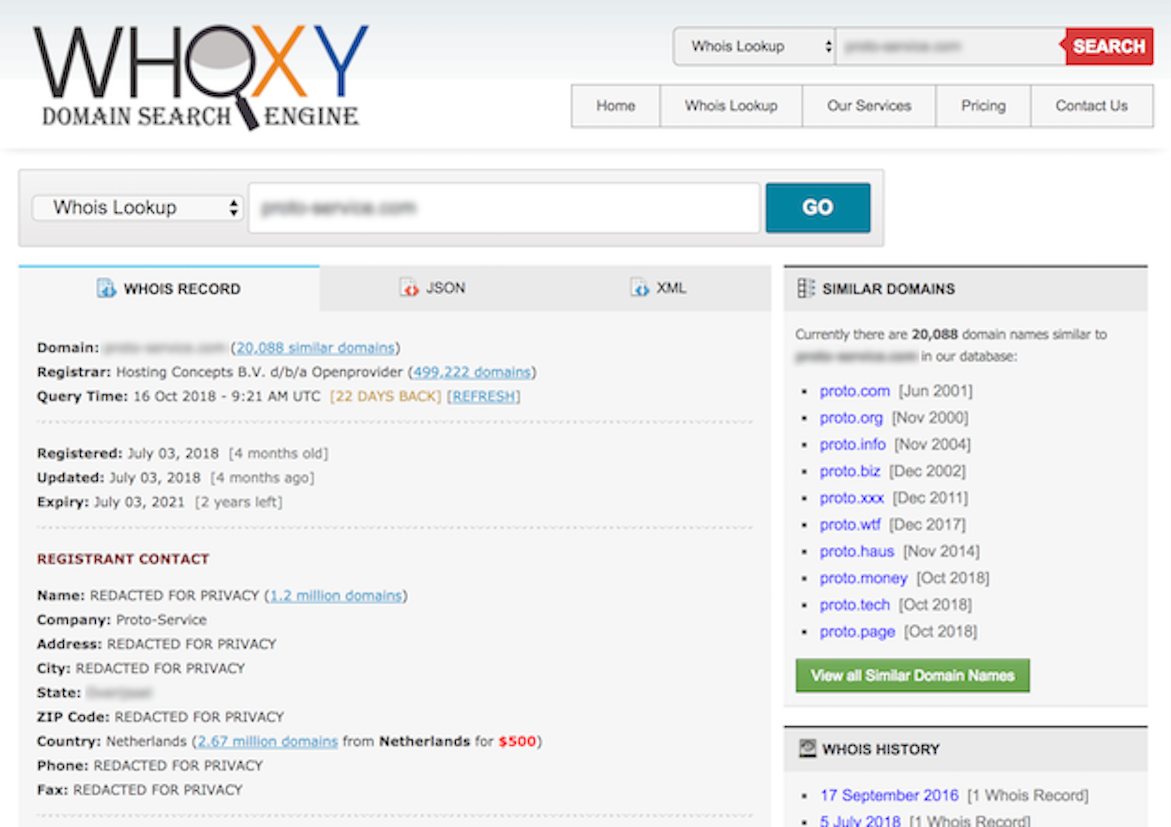

Example 3: GDPR-limited data

A last real life example is a domain registered on the company Proto-Service. Apparently Whoxy.com could not link this company name to any previously collected data, and thus it shows nothing more than “REDACTED FOR PRIVACY”:

What does this show?

Let’s be honest, these are all examples that illustrate our assumptions. You can call it a bias. It does not prove anything, but hopefully, it does explain why we would rather explain “domain spam after the passage of the GDPR” as a result of smart minds than a result of data leaking.

Every example that we hve investigated so far can be explained by the examples in this blog post.

We am still looking for an example that can not be explained in this way: a domain, registered on a unique e-mail address that is used nowhere else, that receives domain-related spam. For example, domain-z.com is registered with e-mail address firstname@domain-z.com, which is published or used nowhere else on the internet. Could it be possible that domain-related spam is received on this e-mail address? We doubt it! But if you encounter this situation, we’ll investigate and pay you a beer!

Oh, and what about the question?

You’re right, the question in this blog post’s title is whether or not the GDPR resulted in a reduction of domain spam. Honestly, I do not know. Despite the title, our intention was to explain the above rather than make a numerical analysis. we w gladly leave that to the experts! For example, one of the leading anti spam agencies, Spamhouse, does not see a clear proof and states it is far too early to tell.